__ _____

______/ |_ ____ _______ _____ _/ ____\ ____ _______ _____ ____ _______

/ ___/ __\/ __ \\_ __ \/ \\ __\ / __ \\_ __ \/ \_/ __ \\_ __ \

\___ \ | | ( \_\ )| | \/ | | \| | ( \_\ )| | \/ | | \ ___/_| | \/

/____ \|__| \____/ |__| |__|_| /|_ | \____/ |__| |__|_| /\___ /|__|

\/ \/ \/ \/ \/ The NeverEnding Story – The Fight Against The Nothing

Much beloved by children of the 80s, and children-at-heart of the current day; the 1984 film The NeverEnding Story dominated my consciousness growing up, and still moves me to tears. Based upon the 1979 novel by Michael Ende, the movie is often regarded in the same high tier as 80s fantasy classics, such as Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal. These movies often share the same, well established nostalgic discourse: celebrating the wonder of imagination. I would like to offer a different, much more radical reading of NeverEnding. To do so, I will start with the ‘classic’ reading, and then journey on into stranger territories.

Would you like to hop on this train ride with me?

Not only does NeverEnding have common and appealing fantasy tropes, it also presents quite an accessible meta-fantasy exploration to make its central, and obvious, moral push. That push runs thus: we must have courage against our despair and use our power of dreaming and imagination to create a new world. Or another version: Grief and loss must be resisted by remembering and enacting our child-like capacity to playfully create new worlds. Simple enough right? Well, maybe. To commence focusing my ‘hot take’, allow me to briefly outline the standard ‘classic’ reading of the movie:

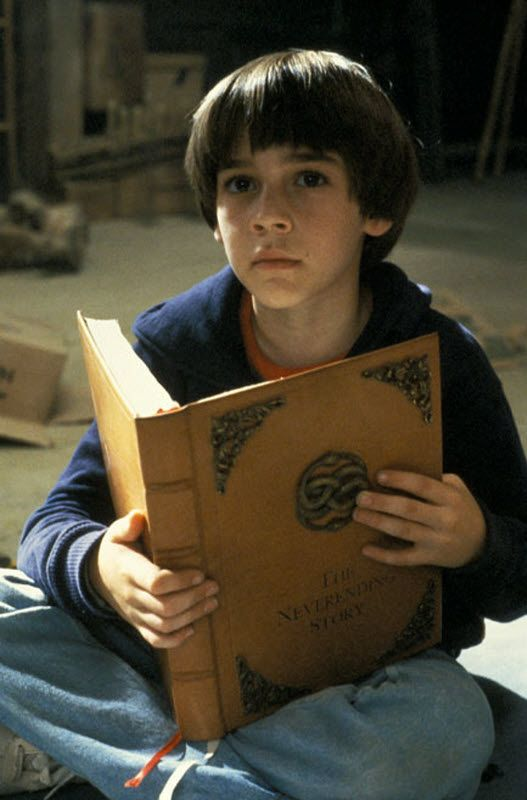

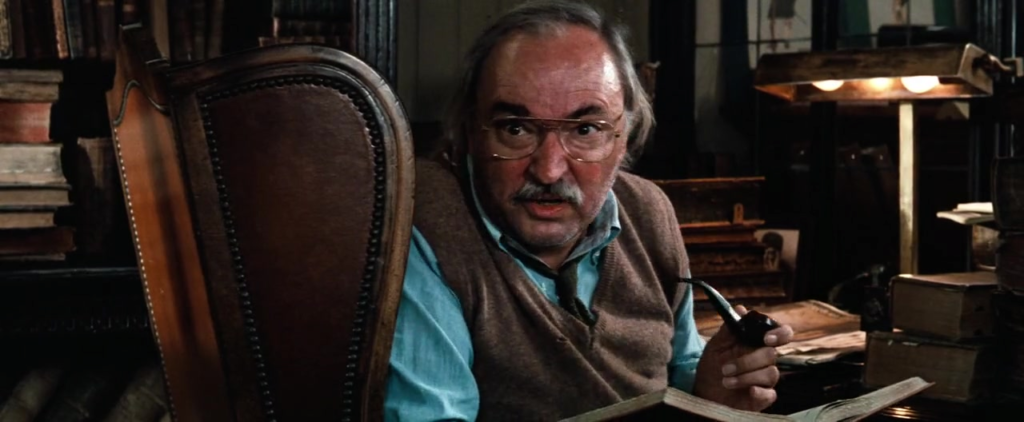

The NeverEnding Story starts with Bastian, a shy and sad boy living with his father in what seems to be a modern white western suburban setting. Bastian is distracted, daydreaming, surviving nightmares and grieving the loss of his mother. The business-like father is disappointed in Bastian’s engagement at school and other activitie. He instructs Bastian to get his feet on the ground and give up the daydreaming. Bastian reluctantly complies, only to be subjected to violent bullying on the way to school. He escapes the bullying by stumbling into an old bookstore, kept by a gruff bookseller named Mr Coreander, whom confronts Bastian by expressing his doubt of Bastian’s commitment to books. Bastian, defensive, shows curiosity in Coeander’s prized book, titled The Neverending Story. Despite Coreander’s warning, Bastian snatches the book away pledging to later return it. Arriving late at school, Bastian avoids more bullying by taking the book up to the school attic, and there he begins to read.

The film then starts a ‘split’ tale of what is happening in Bastian’s book, and Bastian’s reactions to the reading. We are greeted with the fantastical world of Fantasia. Herein we meet wondrous characters that quest to solve the core crisis of Fantasia: “The Nothing” – a malevolent devastating force that seems to be tearing the world and its inhabitants into emptiness. Concurrently, the highest authority in Fantasia, the Childlike Empress, is dying: and her decline seems to be linked to increasing ravage of The Nothing. The characters of Fantasia put all their hopes into a young warrior named Atreyu as the champion of the Empress. Atreyu sets out to find a cure and stop The Nothing.

Atreyu’s quest faces many challenges and set-backs, as well as a bit of good luck – with Bastian reacting predictably and expressively as the story unfolds. Some of these chapters are so powerful they’ve become memes that always appear in the standard discourse around NeverEnding: the horrific anguish of Atreyu losing his horse Artex in the Swamps of Sadness; the unforgettable ferocious joy of Falkor the luck dragon; Atreyu’s courage at the gates of the Southern Oracle; the chilling and violent confrontation with the evil giant wolf servant of The Nothing: Gmork. The film, in my opinion, holds its own against any modern fantasy spectacle. In particular, the apocalyptic stormy annihilation of The Nothing still blows me away visually – am I not the STORMFORMER after all?

As the story progresses, things start to become weird. The line between Atreyu’s world and Bastian’s world begins to blur. Atreyu sees Bastian in a vision, and he is advised by The Southern Oracle to find the Empress a new name from a ‘human child’ as a cure, and thus beat The Nothing. Bastian has a name in mind, but does not speak it aloud. Despite Bastian being freaked out by Atreyu’s vision, he presses on with courage, reading the book well into the evening rather than returning home. Atreyu’s quest seems to depressingly fail with The Nothing obliterating nearly everything, leaving him with just Falkor to take him to the fragile Childlike Empress and report his despair. We meet her at at last. The new name she seeks must not only come from a ‘human child’ – it must come from none other than Bastian! In one of the most incredibly emotional climaxes to a movie, the Childlike Empress cries out to Bastian, appealing Bastian to dare to dream and give her name out loud. Rising to the moment, Bastian cries out the window to the thunderstorm surrounding school, screaming “MOONCHILD!” …And she is saved.

Bastian is then transposed into Fantasia with Moonchild. She shows the last grain of sand left of Fantasia – tasking Bastian to use his imaginative power to make a wish come true, and thus restore Fantasia. Bastian’s euphoria in fulfilling his childlike fantasies is incredible to behold. We see the return of the lands and our beloved characters; even with Bastian transposing back to ‘real life’ with Falkor to finally and justly vanquish the bullies. While the movie comes to an end, we are told by a narrator that the story will continue on another time, hence will be truly NeverEnding.

Most would conclude from the above that this is a straightforward children’s story, urging us to never give up on wonder and imagination, even when we grow into ‘responsible adults’. I think that take is very important, and it’s a big reason why I recommend the film to others. The world needs more Bastians to thrive, more than ever: we have to beat whatever The Nothing is, etc. However, I want to layer a different, deeper reading in addition to this common moral of the story.

Dear reader, it is here where I pause the train of my argument to allow you to alight to the station. The station is safe. It’s been fun sharing some nostalgia with you – so all good if this is where you’d like to stop. No doubt some ardent fans of this classic film will be accusing me of committing the heinous act of headcanon; profanely desecrating the story. I am cool if the following reading is not for you – if so, I bid thee adieu and thanks for riding along thus far. From herewith, my reading of The NeverEnding Story centres around gender.

Allow me to explain as we restart the train.

Firstly, let us look again to the film’s story as it immediately presents itself.

Bastian is introduced to us as a young prepubescent boy, gawky, sad and deflated. He has lost his mother, the only female figure in his life – assumingly for some tragic reason. His struggle is initially met by his father, embodying the role of patriarchal masculinity. Bastian’s father is dressed for business, clean cut, using the technology of the kitchen to efficiently create and devour an egg for breakfast. Meanwhile Bastian has not even the physical strength to open the lid off a jar. The father is mostly pitiless to Bastian’s suffering, instead projecting disappointment upon Bastian, admonishing him for disengaging from education. The father essentially implies to Bastian it is unacceptable to be a ‘sensitive weak boy’ that daydreams to cope with his mother’s death. The father cares not for unicorns – boys are not meant to like unicorns. Bastian’s mop hair gets ruffled by the father in some sort of constricted act of expressing love and encouragement; but this of course does very little to bolster Bastian’s depressed spirit. The father leaves, and Bastian has no one to turn to for comfort, left with no choice but to repress his emotion and get on with the day, just like dad.

On his way to school he encounters boys that contrast him – the bullies. These boys are presented with malignant power and confidence. Their hair, clothing and body movement represent what is expected of modern white Western boys under patriarchy – tough, mean and unrelenting. ‘Proper’ boys. They taunt Bastian while they enact their violence, using the classic trope of calling Bastian a ‘chicken’ and wondering if he will lay an egg in the dumpster. The act serves to punish Bastian as not fulfilling his role as a masculine boy and therefore to know his diminished place under patriarchy. Softness and emotion are to be beat out of the boy in order for him to be corrected to the right path of growing into being a real man.

Escaping to Coreander’s bookstore, Bastian encounters a strangely kindred spirit in the bookseller. Here is an older man, presumably past his physical prime, devoting himself the gentle pastime of reading a fantasy book. Coreander also has, if balding, longer hair than what we see from Bastian’s father. Testing Bastian’s heart and fortitude, stating that Neverending Story book is not ‘safe’ – implying that it carries some sort of power to go dangerously beyond a mere fantasy book. This challenge to Bastian pulls something of himself outward, not only to prompt Bastian to argue that he is a serious nerd too, but also to courageously defy Coreander’s gruffness and ‘loan’ the book without asking. It’s not perfect, but we already see Bastian growing. Ready for change.

Arriving at school late and seeing Bastian retreat to the attic highlights his outcast status, his separate otherness, gone where forgotten junk goes. His inability with mathematics is also his failure to be a ‘proper’ boy – maths is a subject boys are supposed to excel at, as apparently boys are meant to have more objective minds something something something blah blah blah facts and logic? No, instead Bastian indulges his emotions in the book, making a little nest for himself with dusty old gym mats. He dives into reading about Fantasia, safe and free from the gaze of his father and bullies.

We are met with some endearing fantastical characters. Rockbiter, a giant rock-man, pulls up to a camp to meet Teeny Weeny and his racing snail, with Tilo Prückner the night hob and his sleepy hang-glider bat. Rockbiter’s stony might symbolises his masculine strength, but this is contrasted by his evident passion for eating tasty rocks and being expressively concerned about how The Nothing is attacking his people. He, with Teeny and Tilo, is on a valiant mission to go to the Childlike Empress’s leadership, seeking a solution to The Nothing – they all voice their passion freely and openly. Teeny is assumingly a man, but dressed ostentatiously, his voice high and soft. Tilo, also seems not strictly masculine in appearance, dress and behaviour; having wild long hair and lisping.

We ride with them united to arrive at the Ivory Tower – a glowing, ornate and fantastically beautiful palace where resides the yet unseen Childlike Empress. Here are a large diversity of characters have gathered in conference – all sorts of shapes, sizes and characteristics are represented. The Empress, remaining hidden, is represented by a head servant, heralding to the crowd. He appears to be a man, but also strange: wisely aged, dark skin, with long flowing hair and a beard. The introduction to NeverEnding culminates in us meeting the story’s summoned heroic champion: Atreyu.

The great warrior defies our expectations. Not only is he ‘just a boy’, he is astonishingly beautiful. Atreyu’s hair is long, draping around his soft face. He is strong and dressed for action, but even his voice betrays ease with light high notes and a ready kindness. Artex, Atreyu’s beloved horse, is also portrayed with beauty and love – we see Atreyu treating Artex as a dear friend rather than a warrior’s tool. This contrasts with our first glimpses of masculine Gmork, growling with a deep voice, dark and full of hungry rage in his hunting pursuit.

Our hearts are absolutely destroyed as we watch Atreyu and Bastian cry their eyes out over Artex’s near-graphic death in the Swamps of Sadness. The emotion of hopelessness here can be deadly. Atreyu’s screams of pain are unforgettable, and we see his naked despair trudging on in the cold mud and muck. The meeting of Morla the Ancient One swirls with mystery and confusion. Morla appears to be a giant, ancient, somewhat feminine, turtle – bogged for aeons in the swamp. She’s been there for so long she can’t even remember who she is any more, highlighting a recurring theme of characters with confused identity. She can’t remember her name and she refers to herself as ‘we’. She’s allergic to boys, but Atreyu gets the clues he needs for the next stage of his arduous quest: find the impossibly distant Southern Oracle to get the real answers. Atreyu plods on weakly into the Swamps, heavy with loss, until he too seems to be tempting the same fate as Artex. As he sinks into the deadly mud, he shows us emotional desperation, reaching out to some impossible hope of a large white thing flying out of the heavy clouds. As Gmork nips at Atreyu’s heels, of course, Falkor flies in to save the day.

Rescued, cleaned, safe and healing, Atreyu wakes up comfortably nested in Falkor’s protection. Falkor can be big and scary, but we learn with Atreyu that Falkor is also soft – he has a loving kindness and is definitely just a bit silly. (Side note: I’d also argue that Falkor is Artex resurrected, but that’s another story). We also meet the healers, working their esoteric knowledge: Engywook and Urgl. While they seem to fulfil some traditional gender roles; him being the guiding scientist and her being the witchy nurse; they both freely care for Atreyu and want to help. Friendship. Engywook mentors Atreyu on how to pass the first gate to get to the Southern Oracle. The key to passing is to truly feel your own worth while moving through to the other side. We watch a fully armoured, assumingly male, knight figure ride upon a horse up to the gate. The knight seems strong and sure, but the yellow Sphinxes see into his soul and thus death-roast him. So much for fancy pinnacle of masculine power.

Atreyu musters his courage to have a crack at it.

We see the yellow Sphinxes up close. They are hybrid creatures – part human, part beast, part angel. Their naked breasts are fulsome, heaving out prominently from the chest; their ancient deadly gazes are feminine and royal. Atreyu passes, being true to himself, but also not afraid to use his brain and fear to bolt through, narrowly avoiding fatal incineration.

The second gate presents as a psychological test of identity: Atreyu peers into a freezing cold mirror only to see Bastian staring back across realities. Both are surprised at what they see. Bastian panics and initially denies the vision, but like Atreyu, he gathers his courage to come back to the story. This allows Atreyu to pass through the mirror.

The warrior thus makes it to the Southern Oracle: another pair of Sphinxes – this time peaceful, cool and blue. The Oracle answers Atreyu with a collective ‘we’, echoing Morla in challenging the idea of singular self-hood. They reveal the key: the Empress needs a new name that Atreyu cannot provide. As the Oracle urges Atreyu on, the blue Sphinxes crumble – their very selves unable to withstand The Nothing.

As Atreyu and Falkor search for a human child, the day is ending in Bastian’s world, and he wistfully wishes for the characters of the book to ask him for a name. He’s got a good one in mind: the name of his mother. Storms form in both worlds: Bastian’s storm intrudes through the attic window to threaten his fragile candle-light; and Atreyu is separated from Falkor, plunging into the sea, washing up upon a beach. Aghast, he realises he lost the Auryn. The Auryn symbolises more than just Atreyu’s power to represent the Childlike Empress: it’s also like his mojo. Having lost it, his resolve shaken; he panics for Falkor and wanders directionless amongst the ruin.

Under the swirling, looming doom of The Nothing, Atreyu meets Rockbiter in a state of despondent grief. Here a direct quote is important: “They look like big, good, strong hands. Don’t they?” Masculine strength was, astounding to him, not enough to save his friends from annihilation. Atreyu, attempting comfort to Rockbiter, says that he’s the one that’s failed – the once great warrior – but Rockbiter is beyond reach and has accepted that The Nothing will rip him into the storm of oblivion.

Darkness culminates in the meeting with Gmork (my favourite scene of the movie!). In a simmering, deeply threatening weave of evil and reality bending, Gmork explains his completed corruption: in pure servitude to utter destruction, all in order to gain power. I will be bold here and suggest he represents ‘man gone wrong’, the final role manifestation for men under patriarchy. He is the bully incarnate as fantastic lethality. Tellingly, Gmork is defeated by Atreyu’s willingness to let the attack come to him, sub-position himself underneath stabbing Gmork – again showing Atreyu’s thoughtful skill and acceptance of fear and injury. Other warriors would have just attacked.

But it seems all too late, as The Nothing attempts to rip Atreyu away. Luck has it, again, that Falkor rescues the Auryn, as well as our once great warrior.

Riding on hope and a little Auryn-magic, they make it to the Childlike Empress. We see her for the first time. She is small, delicate, vulnerable, dressed in soft white clothes, with makeup and jewellery. As fem as a little girl can be (in white Western culture). While she sits passively in her gorgeously austere Ivory Tower palace, she confronts Atreyu with transcendent knowledge of how the story is climaxing, and Bastian’s real-time role in it. She attempts to sooth, but also confuses. Atreyu can’t help but come back to being the frustrated boy warrior, trying in vain to get the problem fixed. But, The Nothing encroaches even here too, and she becomes alarmed. Tears well in her eyes and Bastian’s, and she then appeals directly to him, her desperation bringing his fear to the surface, urging him out of passivity into commitment. Bastian’s naming triumph is a willingness to find parts of himself that transcend his role as a ‘just a boy’ – he finally embodies empathy, care, courage, action. …And she is saved.

So what? you might ask. Well, bear with me here, dear reader, as I spice it up a little more. Let’s keep this train going shall we?

Secondly (do you remember I said Firstly earlier?), it’s important to look at some of ‘text’ surrounding The NeverEnding Story that, I feel, relates to gender.

If we punch through another wall of reality, then one of our first wishes can take us to the title song from the soundtrack. The vocals are performed as a kind of duet between Limahl and Beth Andersen (whom I feel is a bit underrated here). What still blows my mind is how confusing the gender of Limahl’s singing is – is it a man or a woman? This echoes a question from earlier: Is Atreyu a boy or a girl? Beth woos us with an obvious gentle feminine sound much like how Moonchild is clearly fem. She hints to us a spectrum of possibilities: “And there upon a rainbow”. Limahl also reminds us what our purpose is here: “Show no fear, for she may fade away” [emphasis added]. Is she just at risk of simply being denied by The Nothing, or is that fade away hinting at something more?

To deepen the mystery, let us turn to cinematography. Movie makers use all sorts of tricks to help us feel things while watching a movie. A lot of the time, it’s just mundane technique like ‘shot-reverse-shot’ to help us feel like we’re on the side of a conversation; a wide shot establishes or finishes a scene; a close up ramps up the intimacy and tension; and so on. One of the more daring techniques is the ‘fourth wall break’ where the actor looks straight down the barrel of the camera and delivers the line. Sometimes this is used to simply highlight Point Of View to get us to see what something is like for the character the movie wants you to focus through; or, sometimes it can indicate a lot more.

Quick tangent here: have a look at the fourth wall break in Twin Peaks, where MIKE explains to our heroes that evil BOB is beyond mundane detection, stating: “the true face of BOB can be seen only by the gifted and the damned”. As MIKE says “and the damned”, he thunders the line right into the camera, which I think is director David Lynch’s powerful statement about who we are as the audience members. (Blessed to be damned, thanks David!) That’s bloody art right there.

Bear that technique in mind for a moment while I weave this idea with a second story-telling idea. For as long as dramatic theatrical plays have existed, leading up to modern contemporary film, there is a way you can make meaning of the characters by analysing them as representing ‘parts’ of ourselves. Luke Skywalker is our struggling, coming-of-age hero on a journey; Anakin our tragically fallen golden-child that finds empathy again to overcome evil; Palpatine our hungry will to control; and so on. All these characters are bits of us.

The conclusion of any given story is us completing a psychological process to analyse these ‘parts’ and bring them to healthy integration – to encourage us to let our good ‘parts’ shine through, and the problematic ‘parts’ to be well-managed or let go of. I feel strongly that these ‘parts’ can also represent aspects of our identity, including our gender.

The NeverEnding Story has some vital fourth wall breaks. Consider the following dialogue:

Childlike Empress: Bastian, why don’t you do what you dream, Bastian ?

Bastian: But I can’t ! I have to keep my feet on the ground!

Childlike Empress: Call my name ! Bastian, please ! Save us !

Bastian: All right, I’ll do it. I’ll save you. I will do what I dream!

These lines are supremely acted, delivered with over-whelming pathos, straight down the barrel of the camera, directly into you and me as viewers. She is crying, he is crying, I am crying while writing this, are you crying while reading this?

Now, recall the earlier magic mirror scene, as preparation, where Atreyu sees himself reflected as Bastian, and visa versa.

Now, transpose that strange feeling to the even more powerful fourth wall break of Moonchild trying to get Bastian to let go and accept that she is real.

Now, consider all that, while considering Bastian, Atreyu, Moonchildas all parts of ourselves. This pivotal moment comes after a whole movie of gender weirdness: starting with gender under patriarchal normativity, leading to all this fantasy that has characters going beyond gender norms, deconstructing identities. We come to this three way conversation between the wounded unable-to-conform boy, the young fantasy warrior that has a strong feminine side, to the pure feminine girl. The climatic fourth wall break, like cracking a stubborn eggshell, deeply challenges us, asking: what are all these gendered parts of ourselves? Why are we analysing this of ourselves? What’s going on here?! Why is a new name so bloody important?!

Here, my dear reader, I now come to the heart of my argument:

Bastian is transgender.

Born into a body incongruent with her true gender identity, Bastian is forced to deny that part of herself. Her father plays out her inner cis-normative internalised transphobia. The bullies represent the same, but more as violent self-denial. Bastian is marginalised by her peers and the school system, so she turns to fantasy and dreaming to cope, but not yet ready to go beyond her ‘safe’ fantasy to actual real transitioning story-creation. She’s still an egg in a dumpster. The old bookseller is a warning from a possible future: she could end up as a grumpy old man regretting her lack of courage. The characters of Fantasia show Bastian that genders are diverse, that she can explore possibilities beyond what the mundane imposes upon her. Atreyu is Bastian making an actual attempt to make sense of her gender – it’s not quite defined yet, a bit of boy, a bit of girl… is Limahl’s voice a man’s or a woman’s? Artex is shed from Bastian, violently, as she no longer needs the pure beastly muscle of the boy-warrior. Morla is another warning within Bastian – would the girl inside her end up lost and without identity? Falkor is many things within Bastian, mostly representing her growing acceptance that she is agent in her own change, and a ‘hybrid creature’; both luck and dragon; transformed beyond a mere horse. Similarly, the Sphinxes are the non-binary part of Bastian’s transness – she (or they) cannot transition unless she is true to herself (or themselves). The dead knight is a warning that a lifetime of faking who she is leads to death. Rockbiter is Bastian’s despair of trying to mask and perform maleness, as that was what she was ‘assigned’ with at birth – her strong, testosterone-aided hands are not enough against The Nothing – tightening her grip only accelerated the loss. Gmork is Bastian’s potential for full living denial of the truth of her trans nature, a denial that could run its course into violent toxic masculine harm. Bastian uses Atreyu to kill Gmork, so that her capacity for self destruction is slayed. Even The Nothing, the empty formless evil behind it all, is Bastian’s inner demon that eats away at her ability to form herself. Bastian’s triumph against The Nothing is the embodiment of her will to formation. After the storm she is formed.

Finally, we come to Moonchild herself. Bastian works to finally vision herself completely. When Bastian, teary-eyed, peers across the boundaries of reality to see Moonchild, she is looking at herself, saving herself. In order to commence transition, she must choose a name. To honour the memory of her mother, Bastian screams “Moonchild!” as her first true act of self-formation.

…And she is saved.

Let’s take a deep breath shall we?

So. Why write all these words just to headcanon a transgender reading upon an old kid’s movie from 1984?

I first saw The NeverEnding Story some time during 1985 or 86 (I was 5 or 6 at the time), as it was a beautiful gift in the form of a VHS tape from my maternal grandfather – the tape was played so many times it wore out. In so many ways it had a profound effect on me. I would cry along with Bastian and Atreyu. I even looked a little bit like Bastian.

But then, times change and instead of watching kid’s movies I was listening to Nine Inch Nails, busy trying to awkwardly rebel. As an adult I’d occasionally do a re-watch with friends and partners, but be fairly unfazed by it. Then, a long gap of not seeing it at all. Then, maybe sometime I can’t remember exactly when within the last 12 years, I finally saw it again, and Moonchild’s naming scene brought a rare tear to my eye. It also brought up a lot of complex feelings I was trying very hard to not look at.

Fast forward to now, the middle of August 2024 and the end of winter here, spring just around the corner: watching, or even thinking about The NeverEnding Story makes me well up and cry rivers of cathartic tears. It stares right into my soul. There’s a reason why it’s my favourite movie ever and I am no longer in denial of that fact. The train has arrived. It’s time.

I am transgender.

Pleased to meet you: my name is Mika Former, and I go by she/they pronouns. Mika is pronounced with a high “ee” sound, much like the name Millie or Pikachu.

I am non-binary in my gender, as well as being ‘trans-fem’.

I am also, and most importantly, EXCEEDINGLY FUCKING HAPPY!!!

If you’re a family member or friend, finding this out for the first time, and wrestling with shock, grief and transphobia; please hear me simply with the following two points:

1. Your feelings are valid. Please feel free to get support from your local or state-based trans-ally / LGBT+ support service, as these days there are better and healthier guides to help people through this together, with love and understanding.

2. Read or consider in good faith any solid evidence-based material to question internalised transphobia. Anti-trans brainworms are still a major problem in the world, and they are a weird bummer. They take time to challenge. Seek out representations of trans joy – I can assure you that it’s a very real thing and not to be missed! Share that joy with me!

I decided to face my fear, getting my feet off the ground, during November 2023: committing to seeking out gender affirming care via expert, registered, professionals to help me attempt a feminising transition. I was in the incredibly privileged position (which I’ve worked hard to get to) of being able to commence hormone replacement therapy (HRT) on Saturday the 4th of May 2024. May the 4th be with you! As of the time of writing, changes with my body and psychology are well and truly underway. Transition is a slow, complex, multifaceted, individual process that can physically take 7-10 years, but I am undeniably on my way. I am being formed.

All the signs were there for as long as I can remember, but previously I had not the terminology, education and insight that I have had in last decade. If you had asked me, at Bastian’s age: would I like to take a magic pill and wake up as a girl the next morning? The answer would have been YES. It has always been YES, but I have not been physically and emotionally safe to actually transition up until very recently; although in my mind I can hear Bastian, saying with her lovely fem voice, that anything decent and worthwhile is truly not ‘safe’. I had been long living in that ‘dumpster’ with my ‘egg’ that didn’t start to slowly crack open during the COVID-19 pandemic.

You know how it went during that time. Many of us stuck at home far too much to be psychologically healthy, doing a lot of introspection, spending a lot of time on the internet. I’d like to say there was one almighty egg-crack moment, but it was more like billions of ‘maybe I’m not a bloke?’ thoughts every day of my life, coming into focus during lockdown. Although, I will concede that watching Abigail Thorn’s coming out youtube video was a fairly massive crack. Oh Abi!

It has become easier and easier to make sense of who I was and who I am becoming. I’ve forever encountered girls and women and had the ceaseless wish to be them. I loved the lively colour of girl’s clothing, or girls being goth; the jewellery, the hair, the makeup; but I couldn’t go into those worlds. I’d force myself to stop daydreaming. When very young I was sensitive, more so than anyone I knew. I moved and situated my body sometimes in feminine ways, only to have that taunted or actually physically beaten out of me. I grew up in a reality full of violence. I was bullied for crying about my soft animal toys. I was bullied for being supposedly ‘gay’. I learned quick that this ‘part’ of me was not allowed, not to be spoken of, to be pushed down and controlled. I masked. I tried to fit in and failed a lot at it. My male friendships were often tinged with an air of depression. I was the nerdy, lanky, gawky, boy that couldn’t live up the status that my masculine friends often excelled at. My refuge was music, movies, books, and anything that secretly, privately, allowed me to feel stuff. In the 90s I got into counter-cultural phenomena, all of which had the common, if not mostly subtle, thread of challenging gender norms. All my cultural heroes bent gender.

In denying femininity, I became alienated from it, so I was behind on developing healthy relationships with women, starting to slowly become like Gmork and embodying traits of toxic masculinity. I later did active work on myself to start to fight against that tide, but later in life I overcompensated by donning the ‘white knight’ role. And we now all know what happens to fake knights that approach the yellow Sphinxes – the act continuously collapsed in on itself.

There’s a ‘part’ of me that I’m still learning to deprogram that wants to apologise for existing all the time. That unhealthy part, wants to say “sorry” to all past, pre-transition, friendships and relationships – but a wise person has modelled to me recently the art of being unappologetically me. So, my dear, I am not sorry. And I understand why things didn’t work out. It’s taken me a very long time to figure myself out, but all these things play out this way because they have to, as it’s part of the process of challenging the bullshit that gets shovelled into our heads as we grow up. I will work at being my true, authentic self – if others have a problem with that, then that’s on them and really has nothing to do with me. If that means some connections die, then it is what it is. I want my life to be free of drama. I’ve done more than enough. I am good enough.

Transition is not easy – here is not the place to go into all the gritty private details. I have an awkward second-puberty ahead of me that will no doubt have challenges, hiccups, set-backs, and mountains of dysphoria. It’s hard pushing against the learned habit of pretending to be a bloke for 43 years, a bit like to trying stop an avalanche by flapping a feather. Nevertheless, I’ve done a lot of psychological work on myself over the past year or so, and while my new baby-bird-legs are still a bit wobbly, I now dust myself off, and keep trying despite the fear. Keep going and she will be saved. It’s better than ending up like Coreander, or Gmork.

I prefer to focus on gender euphoria as a radical act. During November 2023 I went to the first of several Saturday protests in the city to scream resistance against the genocide of Palestinians. Those, my dear reader, are people with true courage. As I saw the solidarity mustered in the face of total horror, I realised I am so very privileged, and my little drama is really nothing compared to the strength and will of Palestinians to survive. It was that moment I knew I had to transition, no matter what. Being yourself, sometimes, is an act of defiance, even more so when you’re happy with who you are. Palestinians deserve to be themselves in peace, not live and die under settler colonial oppression. If good people can stand with the Palestinians against insane odds, then I feel it is my duty to be standing authentically too, moving towards euphoria despite the grim absurdity. It’s a euphoria that says to the death machine: “fuck you” and smiles!

Every little breakthrough, step by step, just keeps the waves of happiness rolling in. It’s starting to move rapidly now, faster than I anticipated. Makes sense right? If you learn a new skill that makes you proud of yourself, you naturally want to do more of it. Euphoria is also embodied and psychological – I’ve had frequent moments of tingling, giddy joy. Jumping around home in a dress like the silly girl I wish I could have been. And happy-crying. Happy-crying is incredible! My emotion is much closer to the surface, so I can better process things – I no longer have to rummage through a closet (or dumpster) of man-junk just to find a half-forgotten feeling.

So. What does this mean for my music, my work as an artist? As I’ve already put work out there to the public, using my birth-name, I can’t live in denial of what that is. Those amateur works will remain floating about out there, just like old pre-transition photographs. And I’ve struggled at finishing work for so long now, I’m actually erring cautiously from promising that anything will ever be released. I’ve literally hundreds of songs I could finish and put out there, but I think I now better know why I have have not been completing. It’s because of my voice. I’ve always been frustrated as a singer, but now I know it has been because I’ve never accepted that I could learn my feminine voice. Speech pathology is now part of my transition work, so it will be interesting to see if this can translate into singing. So much of my past music has really just been me stuck in a male body and psychology, processing that pain through music. Now that I’ve started transition, I’ve strangely not felt as much of a need to make sense of emotions through songwriting. Part of being trans and non-binary is being ok with indefinites – maybe I will make finished music again, maybe I won’t. And that’s ok.

So before I give into any more temptation to write out my whole life’s story, I’ll try to wrap up here.

The Nothing is that thing, unique to all of us, that we must fight against, whether it be depression, death, illiteracy, genocide, extinction, the mundanity of evil, toxic masculinity, or internalised transphobia. May you keep on strong with your struggle against it, whatever your path may be. I’m doing the same. This train trip really never ends.

The NeverEnding Story may or may not be a secretly transgender story. It most likely isn’t, and this is just some fun and silliness. But when I watch it, I see it as being transgender as fuck. When Moonchild and Bastian look at me through the camera; they are each other and I am them; they are me as my ‘parts’. We cry together, and we move together through the pain to find the courage to finally, truly, say: Mika.

…And she was saved.